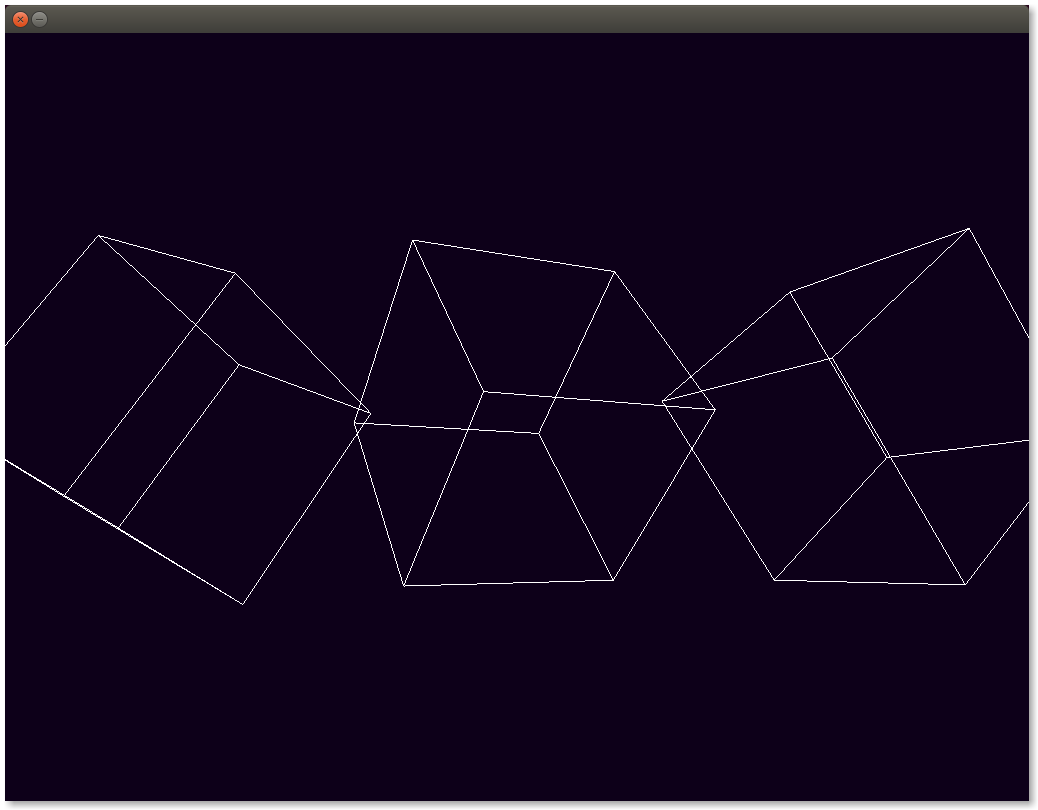

The Wired Swirling Cubes

27 Jun 2014Target

This time our aim is to replace the dull triangle with three wireframe cubes placed one next to another, all in our current view. They should slowly rotate on all axes around their center geometrical center with different amounts and the application should close once 5 seconds pass.

Design

As opposed to last time, we now deal with something more than a simple triangle, namely with structured objects which in 3D parlance are called meshes. Welcome our newest discovered entity, the humble Mesh. A mesh consists of vertices and facets which are used for storing geometrical data.

Quick 3D slang recap:

- a

Facetis a polygon representing a surface. A mesh has many facets.- an

Edgeis the line that defines the zone where two facets meet. A mesh has many edges. Usually you can even calculate how many.- a

Vertexis any corner point between two facets. A mesh has many vertices as well. The plural for vertex is vertices

Ok, let’s get back to describing how we would like the code that implements the requirement to look like, without touching the implementation.

First of all let’s see how the main loop looks like:

int main() {

Window window(800, 600, WindowType::Windowed);

CubeScene cubeScene;

Timer timer;

while (timer.secondsSinceStart() < 5) {

cubeScene.update(timer.lap());

cubeScene.render();

window.present();

}

return 0;

}I decided to keep things simple and create a CubeScene that knows how to create the meshes, update and render them accordingly. I’m doing this so that we don’t pollute the main’s context with so much dirt.

Can you spot a new method on the Timer? Yes, you’re right, it’s timer.lap(). But what does it do and why is it there? It returns the time in seconds that elapsed since method’s last call. I named it like this because it reminds me of running athletes’ lap timer.

In our usage it basically tells you how much time has elapsed since last frame was rendered and we need that in cubeScene.update() because we want to rotate our cubes at a frame-rate independent pace. Thus, no matter how our frame rate varies, we can take the frame time into account and make sure to adjust the rotation amount accordingly so that we perceive the rotation as constant.

Hewh. That was easy! Let’s see what CubeScene interface looks like. We identified a couple of methods already update() and render() and of course an array of meshes.

class CubeScene {

public:

CubeScene();

void update(double secondsSinceLastUpdate);

void render();

private:

Mesh meshes[3];

};Remember we are lazy? We don’t want to explicitely have to call a method to initialize those meshes as cubes so we will make use of CubeScene’s constructor for that task. When we declare a CubeScene instance its constructor will automatically run and will make sure the stored meshes are initialized as cubes and their orientation is randomized.

Oh-oh! Reread the last sentence carefully. Twice. We just might have identified a new entity.

So… we have the Mesh which is a generic entity that contains geometry and someone knows how to fill it with the proper data to make it look like a cube. Let’s call that someone a MeshBuilder and quickly sketch its interface:

class MeshBuilder {

public:

static Mesh cube();

};We decided to make this a helper class with static methods since we are lazy (remember?) and we would hate to build a MeshBuilder instance everytime we need to create a lousy cube. This way we can write neat code like this in CubeScene’s constructor:

CubeScene::CubeScene() {

for (auto& mesh : meshes)

mesh = MeshBuilder::cube();

// ... initialize mesh orientations ...

}Ok, back to our regular schedule, namely the CubeScene interface. The update() method is responsible for updating mesh orientation with respect to the frame time and the render() method is responsible for, well, drawing them meshes. And that’s all there is to the CubeScene for now.

We should move on and see what a Mesh looks like. We have spotted a couple of attributes so far: we mentioned that a Mesh has facets, vertices and edges.

class Mesh {

public:

std::vector<Vertex> vertices;

std::vector<Facet> facets;

std::vector<Edge> edges;

};One more fact that yields from the requirement is that the mesh should also have an orientation and a position. Position because they are placed one next to another and rotation because they… rotate. We will express rotation as a rotation angle around a rotation axis, which is typical for OpenGL.

class Mesh {

...

Vertex position;

Vertex rotationAxis;

double rotationAngle;

};We’re almost there. Few more entities to define:

struct Vertex {

double x, y, z;

};

struct Facet {

int a, b, c;

};

struct Edge {

int from;

int to;

};We defined vertex as a 3D coordinate and that is pretty much the only real spatial data we hold for a Mesh. All other entities are defined as connection between vertices.

A Facet then holds the indices to the vertices that make up its surface. Notice we only have three indices, a, b, c which means we only use triangular facets. Although OpenGL can render quads as well, we decided to only use triangles. This has no other reasoning for now other than my personal taste.

An Edge is also defined by the indices to the vertices which compose it. Just like in the case of facets, we do this indexing thing so that we don’t duplicate vertex information. This should also allow us to do cool things like moving a vertex in time and see the cube distort but still maintain its whole shape.

Implementation

The github repository can be found here. The v1.1 tag contains the code for this post. Alternatively you can download a zip with the sources here. For instructions on how to build and run the code, check the README.md file.